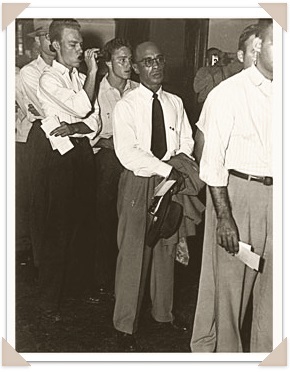

Prints & Photographs Collection, Heman Sweatt file,

The Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

In 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt applied for admission to the University of Texas School of Law, which was at the time an all-white institution. Sweatt met all eligibility requirements for admission except for his race. At that time, Article VII, Section 7 of the Texas Constitution read: "Separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored children, and impartial provision shall be made for both." Based on the Texas constitution, the university registrar rejected his application because Sweatt was black and the University of Texas was a segregated institution. With assistance from NAACP counsel, Sweatt sued in state court, requesting that the court require state and university officials to enroll him. The trial judge continued the case to give the state an opportunity to establish a "separate but equal" law school, and a temporary law school was opened in February 1947, known as the School of Law of the Texas State University for Negroes.

At the School of Law of the Texas State University for Negroes, students had access to the Texas Supreme Court library, and several members of the law faculty of the University of Texas School of Law taught classes. After the establishment of the black law school, the state court dismissed Sweatt's case. Sweatt appealed the dismissal of the case to the United States Supreme Court, claiming that the Texas admissions scheme continued to violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Supreme Court ruled that in states where public graduate and professional schools existed for white students but not for black students, black students must be admitted to the all-white institutions, and that the equal protection clause required Sweatt's admission to the University of Texas School of Law. In the summer of 1950, Horace Heath enrolled in the Graduate School of Government and John Chase enrolled in the architecture program at the University of Texas. Heman Marion Sweatt entered law school at the University of Texas in the fall of 1950, as did several other blacks.

The case had a direct impact on the University of Texas because it permitted black applicants to apply to graduate and professional programs. However, black students could only pursue those degrees that were not available from segregated black universities such as Prairie View A&M University and Texas State University for Negroes, now known as Texas Southern University. Since the University of Texas adopted a narrow interpretation of Sweatt, black undergraduate students were not admitted. Graduate students, however, were allowed to enroll in undergraduate courses when necessary for their program.

At the same time the Supreme Court considered the Sweatt case, it reviewed the policies of the University of Oklahoma in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education. On January 28, 1948, a retired black professor, George McLaurin, applied to the University of Oklahoma to pursue a Doctorate in Education. University authorities were required to deny him admission because of his race under Oklahoma statutes making it a misdemeanor to maintain, operate, teach, or attend a school at which both whites and blacks were enrolled or taught. McLaurin filed a complaint to gain admission. On October 6, the Court for the Western District of Oklahoma found those parts of the Oklahoma statute that denied McLaurin admission unconstitutional, and held that the state had a constitutional duty to provide McLaurin with the education he sought as soon as it provided that education for applicants of any other group. With this ruling the University's Board of Regents voted to admit McLaurin, but on a segregated basis.

On October 13, 1948, McLaurin entered the University. He sat at a designated desk on the mezzanine level of Bizzell Library rather than in the regular reading room, at a desk in an anteroom adjoining Classroom 104 in Carnegie Hall, and ate at a separate time from the white students in the cafeteria. McLaurin once again filed suit, claiming that this segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled that as a result of McLaurin's segregation he was "handicapped in his pursuit of effective graduate instruction. Such restrictions impair and inhibit his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession."

With Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, the Supreme Court began to overturn the separate but equal doctrine in public education by requiring graduate and professional schools to admit black students.

View Case: Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950)