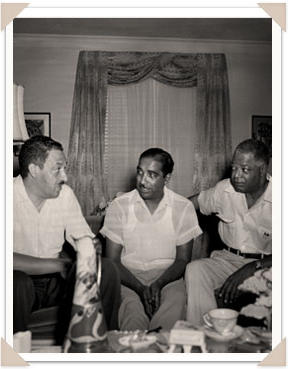

Center for American History,

UT Austin DI Number 01668 Hickman (R.C.)

Photographic Archive, 1949-1961,

1969 Thurgood Marshall, A. Maceo Smith and other

While the decisions of the Supreme Court in Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education led to the desegregation of graduate and professional schools in 1950, many black children continued to be denied admission to white elementary and high schools under state laws either permitting or requiring segregation.

In the fall of 1950, Reverend Oliver Brown attempted to enroll his eight-year-old daughter, Linda, at Sumner Elementary School. Sumner was the elementary school nearest their home in Topeka, Kansas. The principal refused to enroll Linda, who attended all-black Monroe Elementary School, because Sumner Elementary was open only to white children. With the assistance of the NAACP, Reverend Brown filed suit against the Board of Education.

In Clarendon County, South Carolina, schools for black children were funded at only a quarter of the level of schools for white children. The school board did not provide funds for supplies, building maintenance or buses to black schools. Reverend Joseph Albert DeLaine began circulating a petition among the black community requesting the school board provide buses. After the school board refused to provide a bus, parent Harry Briggs filed suit against Roderick W. Elliot, chairman of the school district, in a case known as Briggs v. Elliot.

In Prince Edward County, Virginia, all-black Moton High School was severely underfunded and overcrowded. Barbara Johns, a sixteen-year-old Moton junior, was a member of the school chorus, drama group, New Homemakers of America and student council. In the fall of 1950, she convinced the student council to ask the school board for better facilities for black students. The school board failed to respond, and Johns and the student council organized a strike. For the next two weeks, students picketed outside the school or stayed at their desks with their books closed. The student council contacted the NAACP to request their assistance to pursue legal action. The suit Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County was brought on behalf of 117 Moton students and argued that school segregation in Virginia should be ended.

In Wilmington, Delaware, black high school students were bused to Howard High School, located in a seedy section of downtown. Ethel Belton and her children lived in suburban Claymont, near the new Claymont High School, but her children took a 50 minute bus ride each way to attend Howard. After her children were denied admission at Claymont, Ethel Belton filed suit against the individual members of the school board in a case known as Belton v. Gebhart.

In Washington, D.C., black schools were severely overcrowded, often running double and triple schedules in order to accommodate the students, whereas white schools were half empty as a result of white flight to the suburbs. In September 1950, Gardner Bishop, a local barber and activist, led a group of 11 children and their parents to all-white John Philip Sousa Junior High in an attempt to enroll the children. After the children were denied enrollment, suit was filed against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the board of education, in a case known as Bolling v. Sharpe.

After being denied the relief requested by various federal district courts, these cases reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court consolidated the cases of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kan., Briggs v. Elliott, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Va., and Gebhardt v. Belton. In these cases, the arguments focused on whether the segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprived black children of equal protection of the law as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. Since Bolling v. Sharpe dealt with the District of Columbia rather than a state, the argument in that case focused on whether segregation of the public schools of Washington D.C. violated the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

In December 1952, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in these cases. In an unusual move, the Court requested time for additional oral arguments, which were held in December 1953. In May 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous decisions of the Court in both Brown and Bolling. In Brown, the Court found that segregation in public education had a detrimental effect on minority children because it was interpreted as a sign of inferiority. The long-held doctrine that separate facilities were permissible provided they were equal was rejected. This unanimous opinion sounded the death-knell for all forms of state-maintained racial separation.

In Bolling, the Court found that racial discrimination in the Washington, D.C. public schools denied blacks due process of law as protected by the Fifth Amendment. Due to the legal peculiarities of the District of Columbia, Chief Justice Warren noted that the Fifth Amendment did not contain an equal protection clause while the Fourteenth Amendment, which was the basis of the decision in Brown, did contain one. Lacking an equal protection standard on which to base the invalidation of the District's segregation, Warren relied on the Fifth Amendment's guarantee of "liberty" to find the segregation of the Washington D.C. schools unconstitutional.

In May 1955, the Supreme Court issued an enforcement decree applicable to both Brown and Bolling, commonly known as Brown II. The Court held that the problems identified in Brown and Bolling required varied local solutions. Chief Justice Warren conferred responsibility on local school authorities and the courts which originally heard school segregation cases. They were to implement the principles which the Supreme Court embraced in the Brown decision. Warren urged localities to act on the new principles promptly and to move toward full compliance with them "with all deliberate speed."

View Cases:

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)