It is worth noting that the absence of a woman's name on the title page of an early printed book does not indicate that women were not involved in bringing that book to market. Either through investing, managing, editing, typesetting, or the less visible but no less necessary work of feeding and housing the printers and apprentices, women were certainly instrumental in the craft of printing from its inception.

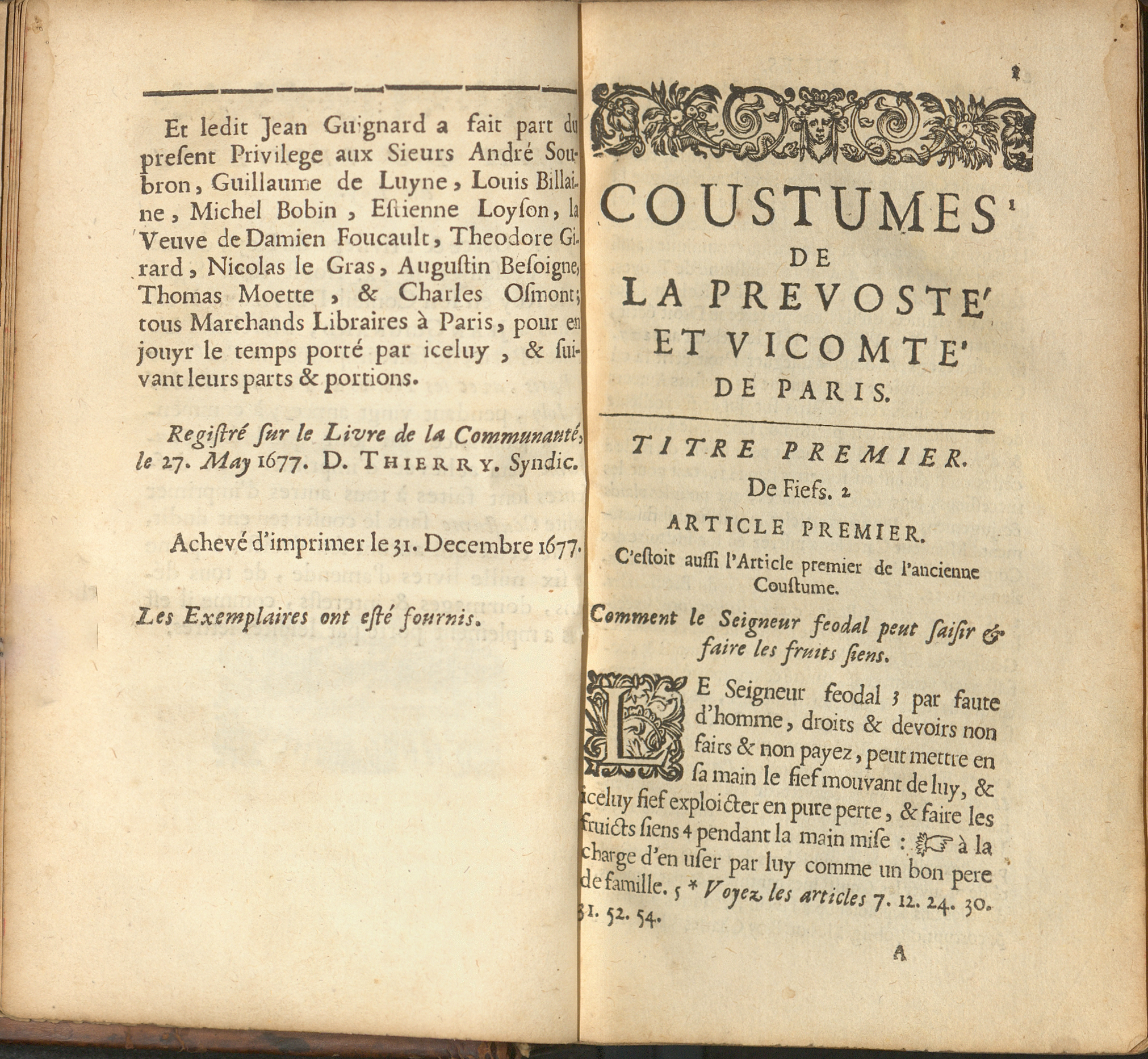

Book historian and bibliographer Sarah Werner has noted that searching the English Short Title Catalog, a catalog of early printed books, for "widow" as publisher returns 352 results- that's a lot of women printers! As widows, women had more agency in controlling their own business and were often reluctant to surrender that freedom for the potential security of another marriage. One example from Tarlton’s collection is this 1678 printing of the Customs of Paris with one of the printers listed as "la Veuve de Damien Foucault," or, the widow of Damien Foucault.

Coustumes de la prevosté et vicomté de Paris : avec les notes de M.C. du Molin, restituées en leur entier…Paris: Chez André Soubron, à l'entrée de la Gallerie des Prisonniers, à l'Image de N. Dame, Avec privilège du roy. Privilège assigned to Jean Guignard, shared…the widow of D. Foucault...M. DC. LXXVII [1678].

The Customs of Paris is a regional compilation of French civil law. It was the customary law of Paris and the surrounding region in the 16th through 18th centuries and was applied to French overseas colonies, making it relevant to the foundations of Texas legal history. The articles of customary law regarding the inheritance rights of widows must have been personally familiar to the widow of Damien Foucault since she had navigated them herself in order to maintain her rights to print this volume.

Sarah Werner. "Finding Women in the Printing Shop." The Collation. Folger Shakespeare Library. October 14, 2014. Web. January 2018.

Helen Smith. Grossly Material Things: Women and Book Production in Early Modern England (Oxford 2012).