When patrons and researchers look through Tarlton Library’s collection of early English legal papers, the term “peppercorn rent” is often remarked upon. The English practice of peppercorn rent is simple on the surface: a nominal rental sum for property, land or buildings. Looking deeper, though, peppercorn rent is a key to the history of English land and real property law.

The earliest reference to peppercorns as consideration, or the exchange of one thing of value for another in contract law in England can be found in the codices of King Aethelred (r. 1013 – 1014) where it is stated that ships delivering to Billingsgate must pay a toll of a ten-pound sack of pepper at Easter and Christmas. After the Norman conquest of England, William the Conqueror (r. 1066 – 1087) declared that all land in England belonged to the Crown, and therefore defined freehold as ownership of an estate in land, rather than the land itself. The land forfeited to William was re-granted by him to be held by his knights, with military service to the crown serving as payment, and eventual entails to ensure that land went to the direct descendants of the freeholders.

The earliest reference to peppercorns as consideration, or the exchange of one thing of value for another in contract law in England can be found in the codices of King Aethelred (r. 1013 – 1014) where it is stated that ships delivering to Billingsgate must pay a toll of a ten-pound sack of pepper at Easter and Christmas. After the Norman conquest of England, William the Conqueror (r. 1066 – 1087) declared that all land in England belonged to the Crown, and therefore defined freehold as ownership of an estate in land, rather than the land itself. The land forfeited to William was re-granted by him to be held by his knights, with military service to the crown serving as payment, and eventual entails to ensure that land went to the direct descendants of the freeholders.

Variations of this theme were tailored for other types of service, as needed. The freeholders, as lords of their manors, received the labor of their serfs and cottagers as payment for use of the land. The Black Death, the bubonic plague pandemic which peaked in England between 1348 and 1349, killed over a third of the population. The resulting shortage of farm labor provided surviving serfs serious bargaining power and they demanded manumission, release from servile duties, or commutation in the form of rents instead of labor. Landlords agreed to accept money rather than services from their new tenants, resulting in the rise of leaseholds, a temporary right to land for a period of time.

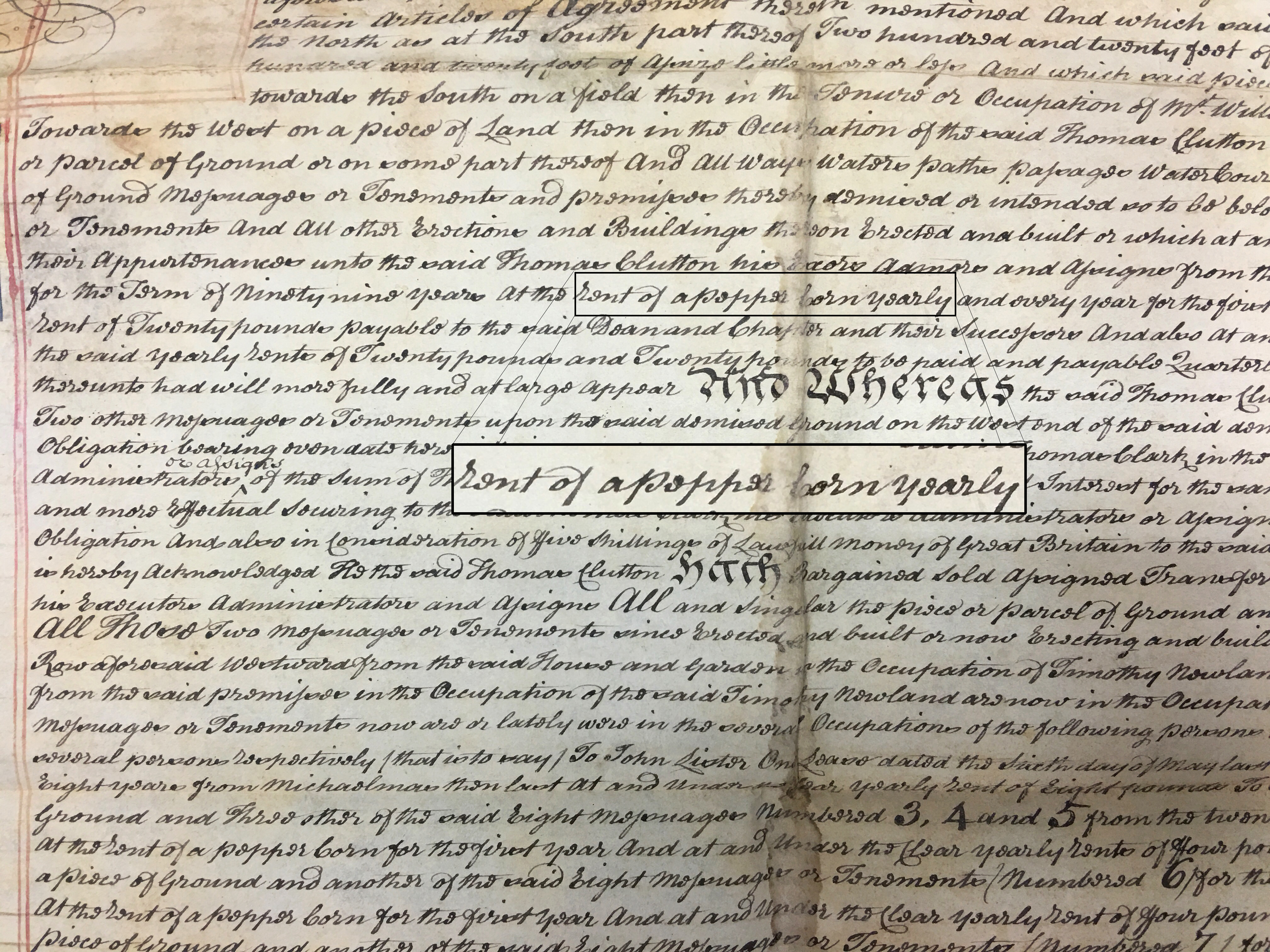

The early English leasehold is not what people generally think of today when leasing property. The shortest leasehold terms in Tarlton’s collection are 5, 10 or 15 years. More common terms are 99 years or 500 years, although there is one instance of 3,000 years. This length of time designates these properties as “virtual freeholds” in which an initial large sum is usually exchanged, followed by a nominal annual consideration, often a peppercorn.

Peppercorns have retained their symbolic value in the English legal system to this day. According to English law, every legal contract requires that each party gives something of value to the other. It is not necessary that the items exchanged be of equal value, but an exchange must take place. A landlord (or freeholder) wishing to rent property basically for free, must still make a contract with the leaseholder for a nominal sum, peppercorn rent.

In Tarlton’s own collection of early English legal papers, peppercorns are joined in their category of nominal rents by “a haunch of venison” to be given at Michaelmas, celebrated on September 29 to mark the end of harvest; “two hens” at Christmas; and, memorably “one red rose” to be given on the quarter days, i.e. Lady Day (March 25), Midsummer Day (June 24), Michaelmas (September 29), and Christmas (December 25).

Peppercorn rents are still in use today, though they are not as common as they once were. The University of Bath currently rents the land it sits on from the East Summerset Council for one peppercorn per year, but other institutions have not enjoyed such generous terms. The Sevenoaks Cricket Club, for instance, built a cricket pavilion on their leased land in the 19th century and saw their rent doubled to two peppercorns. In addition, they must also pay their landlord, the Duke of Sackville, one cricket ball, if asked, on July 21st. Other noteworthy peppercorn rents still in use include the rent of the Billingsgate fish market by the Corporation of London, for which the annual rent is one salmon.

Peppercorn rents are still in use today, though they are not as common as they once were. The University of Bath currently rents the land it sits on from the East Summerset Council for one peppercorn per year, but other institutions have not enjoyed such generous terms. The Sevenoaks Cricket Club, for instance, built a cricket pavilion on their leased land in the 19th century and saw their rent doubled to two peppercorns. In addition, they must also pay their landlord, the Duke of Sackville, one cricket ball, if asked, on July 21st. Other noteworthy peppercorn rents still in use include the rent of the Billingsgate fish market by the Corporation of London, for which the annual rent is one salmon.

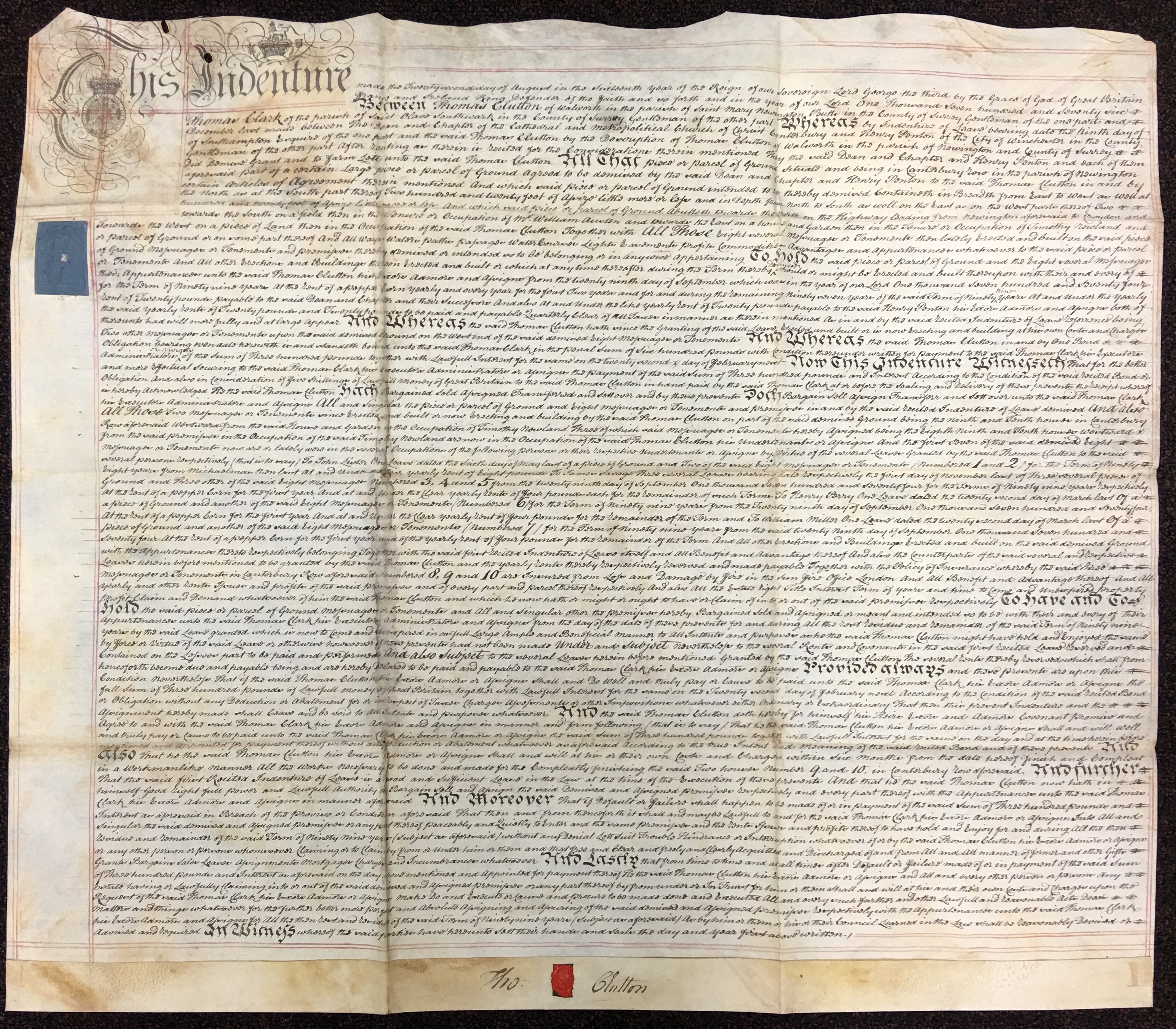

To view an example of peppercorn rent in a legal document, stop by the Special Collections Reading Room on the 4th floor. A framed indenture contract from Tarlton’s Hyder Collection is on display, and the librarians would be happy to point out the peppercorn clause.

Digital scans featured in this exhibit are part of the Early English Legal Manuscripts Collection. Larger images are linked when available. For more information, contact rarebooks@law.utexas.edu.