The most voracious consumers of the legal texts in Tarlton's rare books collection over the years have not been law students but bookworms of another sort. These critters can carve wandering trails across individual pages or tunnel through entire text blocks, cover to cover.

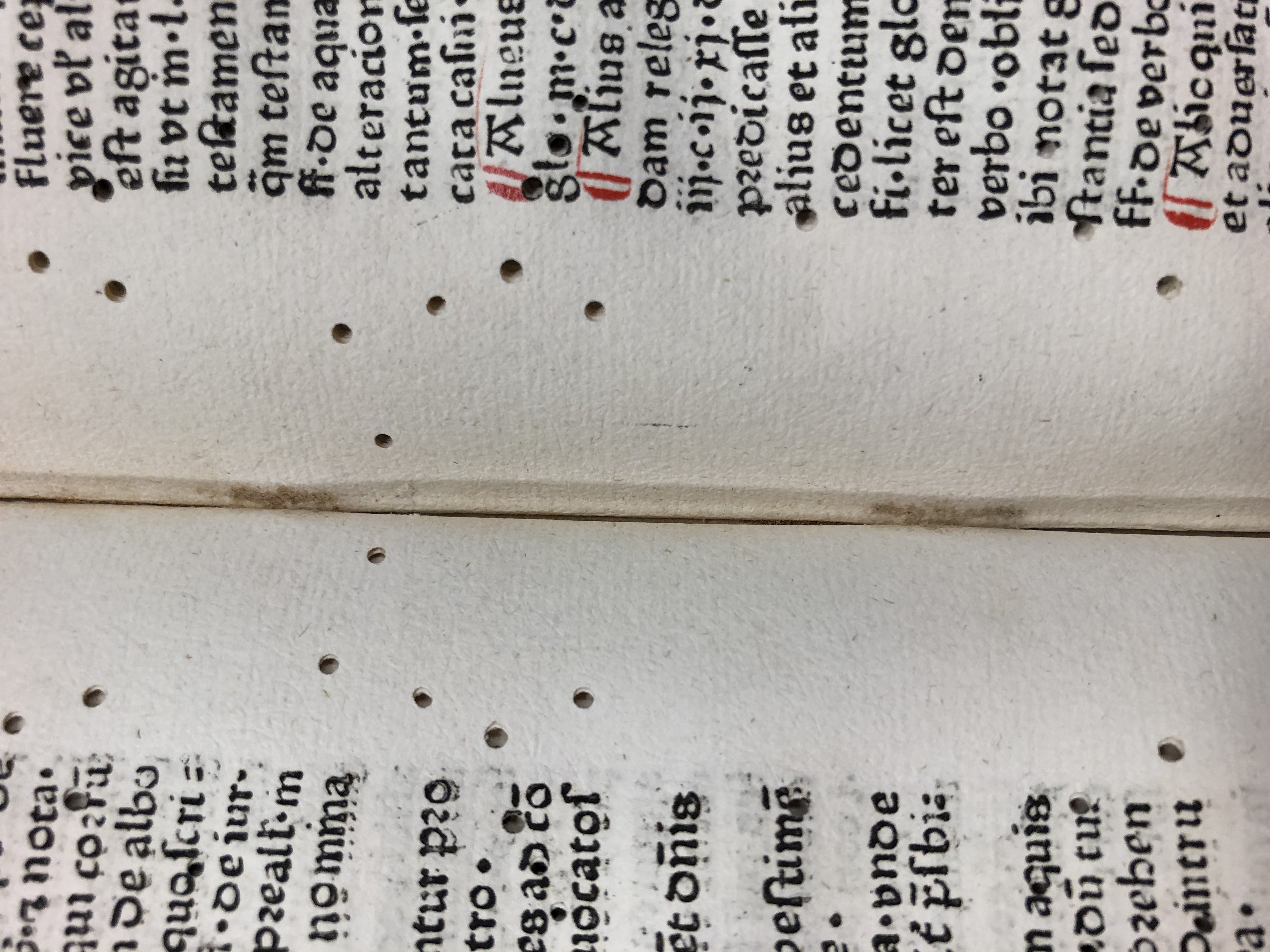

Vocabularius utriusque iuris. [Strasbourg : George Reyser, ca. 1476]

In some instances, such as the first volume of Tarlton's 1712 edition of Pufendorf's De jure naturae et gentium, their paths of destruction can resemble abstract art. Le droit de la nature et des gens : ou, Système général des principes les plus importans de la morale, de la jurisprudence, et de la politique... 2. éd., rev. & augm. considérablement. Amsterdam : Chez Pierrre de Coup, 1712.

Even when not leaving behind such catastrophic damage, bookworms can render text illegible, weaken bindings, and deteriorate paper.

Scholars and librarians have been complaining about bookworms for thousands of years; Aristotle, in Chapter 32, Book V of Historia Animalium, described creatures he had seen chomping through scrolls "resembling tailless scorpions, but very small." And Phillippus of Thessalonica in the first century compared his more studious contemporaries to bookworms, voicing the metaphor now so common that law students touring our rare books collection are often surprised to see the evidence of real rather than metaphorical bookworms.

Actual bookworms aren't worms at all, but beetles. Various types of book bindings and paper attract specific pests; leather bound books are appealing to larder beetles and carpet beetles. Wood and paper are appetizing to death watch beetles. One of the most destructive library pests is the paper louse, probably the creature described by Aristotle.

This tiny insect eats microscopic organic matter found in cool, damp, dark places, like between the covers of your favorite legal treatise.

This tiny insect eats microscopic organic matter found in cool, damp, dark places, like between the covers of your favorite legal treatise.

A previous user of this volume of the Decretals of Gregory attempted to repair bookworm damage with handwritten replacement text pasted over the holes, visible on the third and fourth lines from the bottom of the right column.

This detailed 'patch' job was undertaken on each leaf of the Decretals where text was obscured by wormholes.

Gregory IX (Ugolino di Conti.) Decretalium domini pape Gregorij noni compilatio accurata diligentia emendata summoque studio elaborata et cum scripturis sacris aptissime concordata. Basel: Johan Amerbach for Johannes Froben, 1500.

Modern bookbinding techniques have rendered most publications unappetizing to book-boring insects. Their refined palate prefers the leather and wood bindings, manuscript waste and high cloth content paper of a rare books collection.  Tarlton's rare books are kept in a climate controlled space and the most vulnerable items in our collection are protected with 'phase boxes,' custom sized archival storage boxes or wrapper cases for fragile or deteriorating items in a collection. Phase boxes are particularly helpful for books that have already suffered damage, such as the Pufendorf volume pictured earlier, and again in its phase box here.

Tarlton's rare books are kept in a climate controlled space and the most vulnerable items in our collection are protected with 'phase boxes,' custom sized archival storage boxes or wrapper cases for fragile or deteriorating items in a collection. Phase boxes are particularly helpful for books that have already suffered damage, such as the Pufendorf volume pictured earlier, and again in its phase box here.

Tarlton works to protect our rare books collection from hungry bookworms today, but the damage left by previous generations of insects can provide useful evidence to book historians and bibliographers.

Scientists have extracted bookworm DNA left behind in early books and manuscripts, allowing them to glimpse where and when the books were made and stored.

The size of wormholes left in some texts can help determine the species of the insect, and therefore the manuscript's likely place of origin. These tunnels in the margins of Tarlton's Vocabularius might help a researcher determine where this volume was made, or whether the wood used as its cover harbored furniture beetles when the book was first bound.

The size of wormholes left in some texts can help determine the species of the insect, and therefore the manuscript's likely place of origin. These tunnels in the margins of Tarlton's Vocabularius might help a researcher determine where this volume was made, or whether the wood used as its cover harbored furniture beetles when the book was first bound.

Book historians, working with entomologists, have traced bookworm tunnels across multiple volumes, reconstructing libraries and collections long since broken up and separated and tracing the lives of our books in ways we otherwise could not.

Although they remain unwelcome visitors to the library, the silver lining of past bookworm infestations is the glimpses of the past lives of our collections they can provide to researchers and librarians today.

We look forward to opening our reading room to visitors and researchers interested in experiencing our collections in person again soon, but in the meantime, for further reading on this topic check out some of our sources for this highlight:

Gibbons, Ann. "Goats, Bookworms, a Monk's Kiss: Biologists Reveal the Hidden History of Ancient Gospels." Science, December 8, 2017.

O’Conor, John Francis Xavier. Facts About Bookworms: Their History in Literature and Work in Libraries. University of Michigan Press (1898).

Parker, Thomas A. "Study on integrated pest management for libraries and archives." General Information Programme and UNISIST United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Paris (1988).

Richardson, John V. "Bookworms: The Most Common Insect Pests of Paper in Archives, Libraries, and Museums" Disaster Preparedness. UCLA Extension (2010).

Solberg, Emma M. "Human and Insect Bookworms." Postmedieval 11, 12–22 (2020).

Weiss, H. and R. Carruthers. Insect Enemies of Books. New York: NYPL (1937).